Every day, as I get ready for class, I have to make a decision: to be myself or to assimilate. Though it depends on my mood, I tend to choose the latter. After waking up, I walk straight to the restroom. “I wish it would grow out faster,” I whisper to myself as I look at my reflection in the mirror and run my fingers through my hair. It used to be shaved, but now my hair touches the lower half of my neck.

Then, I wash my face and apply some light makeup. I dab Glossier’s Cloud Paint in Puff across my cheeks, glide Milk’s glitter stick to soften certain features and highlight others, and apply a tinted lip balm for a pinky glow on my lips. I walk to my closet, grab my short-sleeve denim button-up, and put it over my bare chest. The weather is about 72 degrees, a rare sight for Syracuse, so I slip on my black miniskirt. Today, my legs look a little too thick and hairy. But I can’t tell if it’s because of my gender or body dysmorphia. Regardless, I put on long socks to cover my calves and slip on my loafers. I grab my Telfar messenger bag and make my way to my first class.

As I walk on the promenade, people often stare at me. I’ve learned to ignore it — mostly. But certain moments make it unavoidable. Like when someone walks too close or tries to engage. I look away and hope the encounter doesn’t become violent. It hasn’t happened on campus yet, but based on my experiences, I can never be completely sure it won’t. Sometimes stares become harassing howls of transphobic, degrading, or threatening remarks. Other times, it becomes physical, like when a man grabbed my thigh in a park. I just try to prepare myself for the worst.

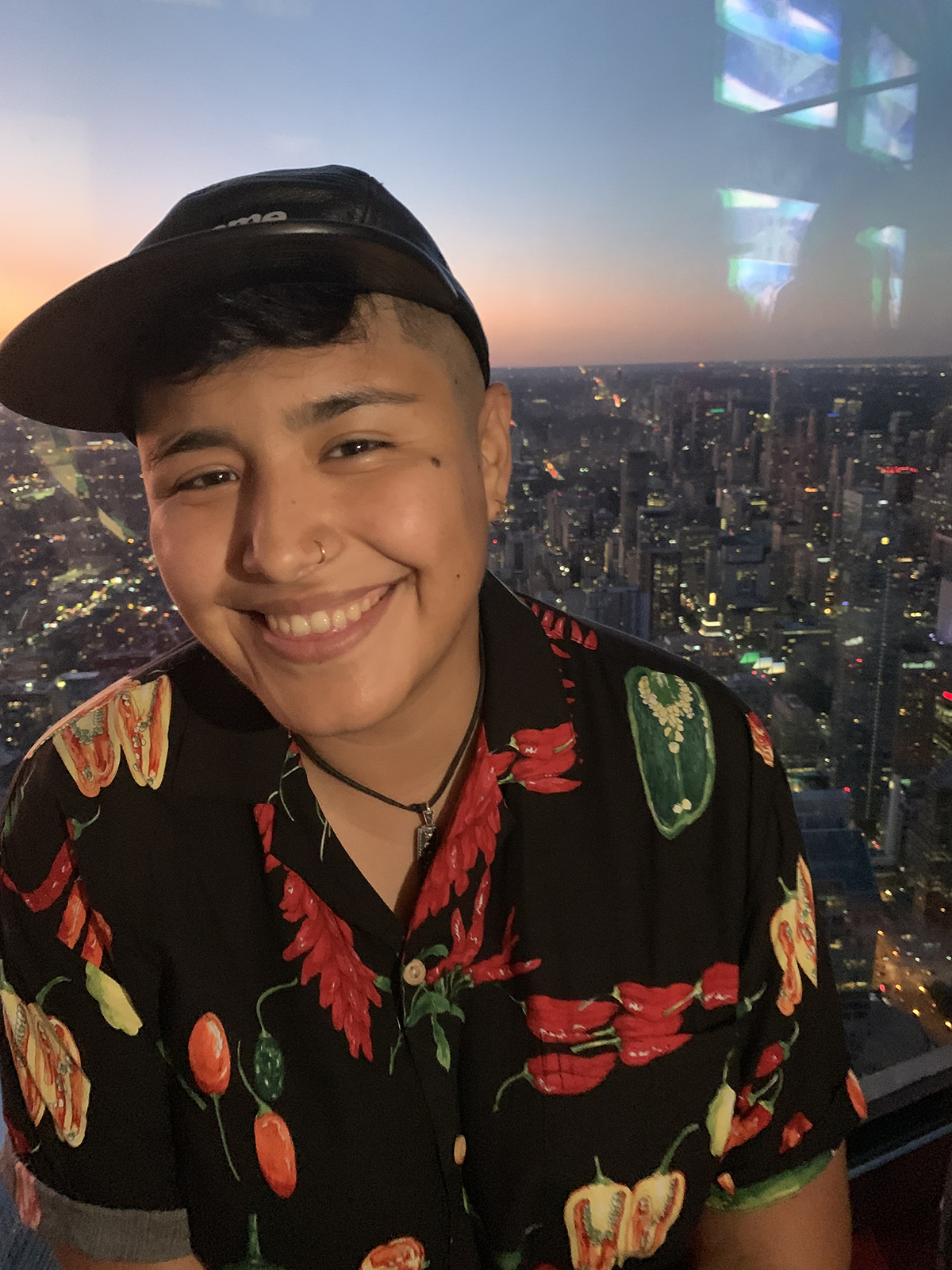

“My name is river now,” I wrote in the caption. “As I began to live my life more authentically, I decided to look towards nature for inspiration. River — a free-flowing source of water that serves as a passage between lakes, seas, and oceans — is an in-between state, with no clear start or end, without restrictions to a binary.” Photo courtesy of River Nguyen Chau.

In my art history class, we’re exploring abstract expressionism. “What do you all think about this painting,” my professor asks about Willem de Kooning’s Woman I. “There’s something oddly misogynistic. There’s an underlying violent, objectifying gaze,” I respond. Another student adds while looking at me: “I agree with him.” I stare at them blankly. The student continues, but all I can think about is being misgendered. I don’t say anything. I don’t correct them. My professor, who knows my pronouns, doesn’t say anything either. I remain seated and stay quiet for the rest of the class.

A Community at Risk

For trans students — students who identify outside of gender norms including those who identify as transgender, gender non-conforming, and two-spirit — this is an everyday experience, and these encounters directly impact their mental health. According to data from the Healthy Minds Study, 78% of gender-minority students reported at least one mental health issue (while about 45% of their cisgender counterparts reported the same). More than 56% of trans students faced debilitating depression (compared to 37% of their cisgender peers), and more than 26% percent of trans students said they considered suicide (compared to 10% of their cisgender peers), according to a survey from the American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment.

“It’s not about being in the TGNB (Transgender and Non-Binary) community that makes you more at risk for mental-health issues,” says Luca Maurer, director of Ithaca College’s Center for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Education, Outreach and Services. “It’s living with constant stigma and discrimination.” Transphobia continues to be a pervasive, powerful cultural force. For example, just in the digital sphere, consider this: A 2019 report by the anti-bullying charity Ditch the Label and consumer intelligence company Brandwatch analyzed 10 million social media and online posts and identified 1.5 million of those as transphobic. “Unfortunately these findings don’t surprise me. For someone who is in the public eye, I experience abuse on a daily basis,” said the British trans model and activist Munroe Bergdorf in a statement responding to the report’s release.

“It’s not about being in the TGNB (Transgender and Non-Binary) community that makes you more at risk for mental-health issues. It’s living with constant stigma and discrimination.”

Issues regarding trans bodies continue to earn mainstream attention. In 2013, when Coy Mathis, a 6-year-old transgender student from Colorado, wanted to use the girl’s restroom, they kicked up conversations around bathrooms that helped fuel change in educational spaces and beyond. In 2019, researchers from Clark University and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst published a study in the Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation based on a survey of more than 500 transgender and gender-nonconforming students and recent grads, asking them to identify policies and accommodations their institutions offered and their importance. The list included 17 services, and gender-neutral bathrooms ranked No. 1. Yet, only 45% of those surveyed said their campuses provided those facilities.

My campus features 73 gender-neutral bathrooms and offers a map and a guide titled Peeing in Peace: A Resource Guide for Transgender Activists and Allies created by the Transgender Law Center. “Bathroom access is not a luxury or special right,” the guide states. “Without safe access to public bathrooms, transgender people are denied full participation in public life.” The guide includes a brief overview of how bathrooms have long been a space where people who possessed authority, power, and wealth denied access to others — including “white” and “colored” bathrooms eliminated by the Civil Rights Movement and the creation of accessible public restrooms for those with disabilities thanks to the Americans with Disabilities Act. “Many people have stereotypical expectations about who will be sharing the bathroom with them,” the guide states. “When they encounter someone who doesn’t fit that stereotype, they sometimes get confused, angry, or afraid.”

45%

of cisgender college students suffer one or more mental-health disorders

78%

of gender minority students suffer one or more mental-health disorders

But as trans issues gained traction, the conversations quickly expanded from who can use what bathroom to whether transgender/non-binary (TGNB) people should be able to take part in the military and have protections at work and if their genitalia alone dictated their gender identity. Trans folk also gained more visibility in the U.S. thanks to pop culture. Laverne Cox became the first trans person to be nominated for a Primetime Emmy for her role as an imprisoned trans woman in Orange is the New Black. When Caitlyn Jenner, known for her Olympic career and Kardashian connections thanks to her marriage to Kris Jenner, came out as trans, she ignited a media frenzy. Pose became the television show with the largest trans cast of any show in history, with trans writers and directors such as Janet Mock, a Black trans writer known for her New York Times best-selling autobiography Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More.

Despite these visibility gains, the TGNB community continues to face discrimination. In March 2020, Idaho’s Governor Brad Little signed a bill banning transgender girls from playing on girl’s and women’s sports teams. He also signed another anti-trans bill that will block trans people in Idaho from changing the gender marker on their birth certificates. Trans people also continue to face violence. According to a 2018 report by the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 52% of anti-LGBTQ homicides in 2017 were committed against trans and gender non-conforming people, and 40% of anti-LGBTQ homicides were committed against trans women of color. In the U.S., Forbes reported that at least 30 transgender women and gender non-conforming folks, a vast majority of whom were women of color, were murdered in 2019 alone. And 331 trans people were murdered, hung, or lynched globally that same year. This figure, while jarring, does not account for the incidents that are unreported, misreported, or the suspicious circumstances in which trans women vanish.

How Misgendering Damages Students

These societal issues impact trans folk experiences at college and undermine their success along with their mental health. While trans students share a unifying identity, each trans student is different, with unique personalities, strengths, and challenges. Yet, many face similar issues: Being misgendered in the classroom, living in assigned housing can be difficult if their roommate is transphobic, and finding counseling services to support their needs. “The reality is that gender-binary discourse goes beyond sex-segregated bathrooms, sex designations on forms, or sex-segregated leadership activities,” said Z Nicolazzo, author of Trans* in College: Transgender Students’ Strategies for Navigating Campus Life and the Institutional Politics of Inclusion, in an interview with Inside Higher Ed. “Although it definitely includes these things, it also is about the very way cisgender students, faculty and staff think gender into — or perhaps more to the point, out of — existence.”

“Calling people their right names and pronouns, I don’t see it as political correctness. I see it as suicide prevention.”

Much of the time, transphobia — whether it’s microaggression, aggression, or just disrespect — remains unchecked. “People will be going to classes and their professors won’t use their pronouns or their professors will be endorsing transphobic views or asking the class whether trans people are real or not,” explains Kai Thigpen, a licensed social worker at the Mazzoni Center for LGBTQ Health and Well-Being located in Philadelphia. These experiences erode well being. Research demonstrates that when chosen names are used, odds of depression and suicide decrease. A 2018 study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health interviewed 129 youths in the Northeast, the Southwest, and the West Coast and found that young people who could use their name at school, home, work and with friends experienced 71% fewer symptoms of severe depression, a 34% decrease in reported thoughts of suicide, and a 65% decrease in suicidal attempts.

Genny Beemyn, director of the Stonewall Center at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and coordinator of the LGBTQ advocacy group Campus Pride’s Trans Policy Clearighouse, believes colleges need to require gender-minority training for professors and staff similar to that required regarding sexual harassment. “Is it any wonder that trans students have mental-health issues when they are typically denied the ability to be seen as how they see themselves on a daily basis?” Beemyn said in an article about the mental-health struggles of trans students. “This means making sure that students are able to use the name they go by and are treated as their gender throughout the institution. Students need to be able to indicate their gender and have this gender be used for housing assignments and sports teams. They need to be able to indicate their pronouns in administrative systems and have these pronouns respected.”