In August of 2018, Morgan Markowitz packed up three suitcases and flew from Las Vegas to Syracuse, N.Y. She hauled those three suitcases up to the un-air-conditioned, eighth-floor dorm in DellPlain, and opened the door to her new bedroom and new life as a college freshman.

Her roommate, another freshman whom Markowitz had met on Facebook, had moved in — to both sides of the standard, open-double dorm room, rearranging the furniture to meet her needs. “I walked in and met her,” Markowitz says. “I had such a bad feeling immediately. Just from meeting her, I was uncomfortable.”

Over the next few weeks, sharing a room would become much more unpleasant than Markowitz expected. Her roommate’s stuff began to creep across the room, leaving Markowitz only a trail from her bed to the door. She locked Markowitz out of the room, and yelled at her for entering their shared space. Her roommate’s significant other was in the room a lot. Markowitz began to spend most of her time in the dorm’s lounge area.

One evening, Markowitz sat in bed, watching Netflix on her laptop with her headphones in. When she closed her laptop, Markowitz realized her roommate was having sex while Markowitz was in the room.

This happened three more times, and Markowitz couldn’t take it anymore.

She approached her resident advisor, her assistant resident director, and the housing administration, but a solution was a long way off. “I felt like no one was taking my situation seriously,” Markowitz says.

Markowitz cited the roommate agreement that both roommates signed when they moved in. The assistant resident director told her those agreements couldn’t be enforced.

McKenzie Rondeau, a former resident advisor at Sacred Heart University and current graduate student in social work at Rhode Island college, referenced her experience with roommate contracts, saying they are often more well intentioned than effective. “Sometimes [roommate contracts are] just a good place for conversation,” Rondeau says, mentioning that universities usually encourage roommates to work through their conflicts before looking for other housing options. The process to switch rooms can take several weeks, depending on the availability of rooms, and often requires parent involvement to see immediate change.

As Markowitz waited for a new room, she started losing sleep, spending her evenings crying in the hallway, and looking up flights back to Las Vegas. She began to feel depressed and anxious, avoiding her room at all costs. In addition to the issues with her roommate, the filth of their room and the old dorm carpet started making Markowitz sick.

“I considered transferring or leaving school, but I didn’t have the financial options to move out of the dorm,” Markowitz says.

“There are many characteristics of housing that can influence mental health...Those can all lead to issues around stress, mood, and mental-health outcomes.”

After multiple conversations, five formal meetings, and a phone call from her mother to the Chancellor’s office, Markowitz received some good news. On November 9, 2018, two and a half months after starting classes, Markowitz switched dorms, moving all of her belongings in an hour when she knew her roommate would be somewhere else.

After moving dorms, Markowitz began to settle in, finally finding comfort in her living situation, but her anxiety skyrocketed. She avoided her former roommate in the dining hall and around campus, worried about a volite interaction. “When we started new classes in the spring, it terrified me that we would be in the same class,” Markowitz says. “I still have a lot of fear about that.”

Markowitz is just one of the many college students who become trapped in unhealthy living situations because they lack the financial resources to move out and the slog of university bureaucracy. In fact, Makowitz is one of the nine million college and graduate students who lack consistent and secure housing in the United States.

The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice at Temple University conducted the “#RealCollege 2020” survey, finding that in 2019, 46% of college students were housing insecure and 17% experienced homelessness in the United States. Housing insecurity prevents students from enjoying a safe, affordable, or consistent place to live. Students often face challenges such as the inability to pay rent and utilities or having to move frequently. Students who experience homelessness lack fixed, regular, and adequate places to live, often staying on friends’ couches temporarily. The survey also reported that lack of secure housing "is associated with self-reports of poor physical health, symptoms of depression, and perceptions of higher stress."

Earle Chambers, Ph.D., is a professor in the departments of Family & Social Medicine and Epidemiology & Population at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York. He studies how the physical environment and social interactions influence health and behavior. “There are many characteristics of housing that can influence mental health,” Chambers says, referencing maintenance, community access, and location. “Those can all lead to issues around stress, mood, and mental-health outcomes.”

In addition to the mental impact of housing insecurity, students also deal with the financial stress of housing, paying a steep price for a clean, comfortable, and welcoming place to live. While a national average cost of student housing is difficult to calculate due to differences in housing types, amenities, quality, and geography, the National Multifamily Housing Council and Axiometrics estimates that students pay about $10,000 annually in rent.

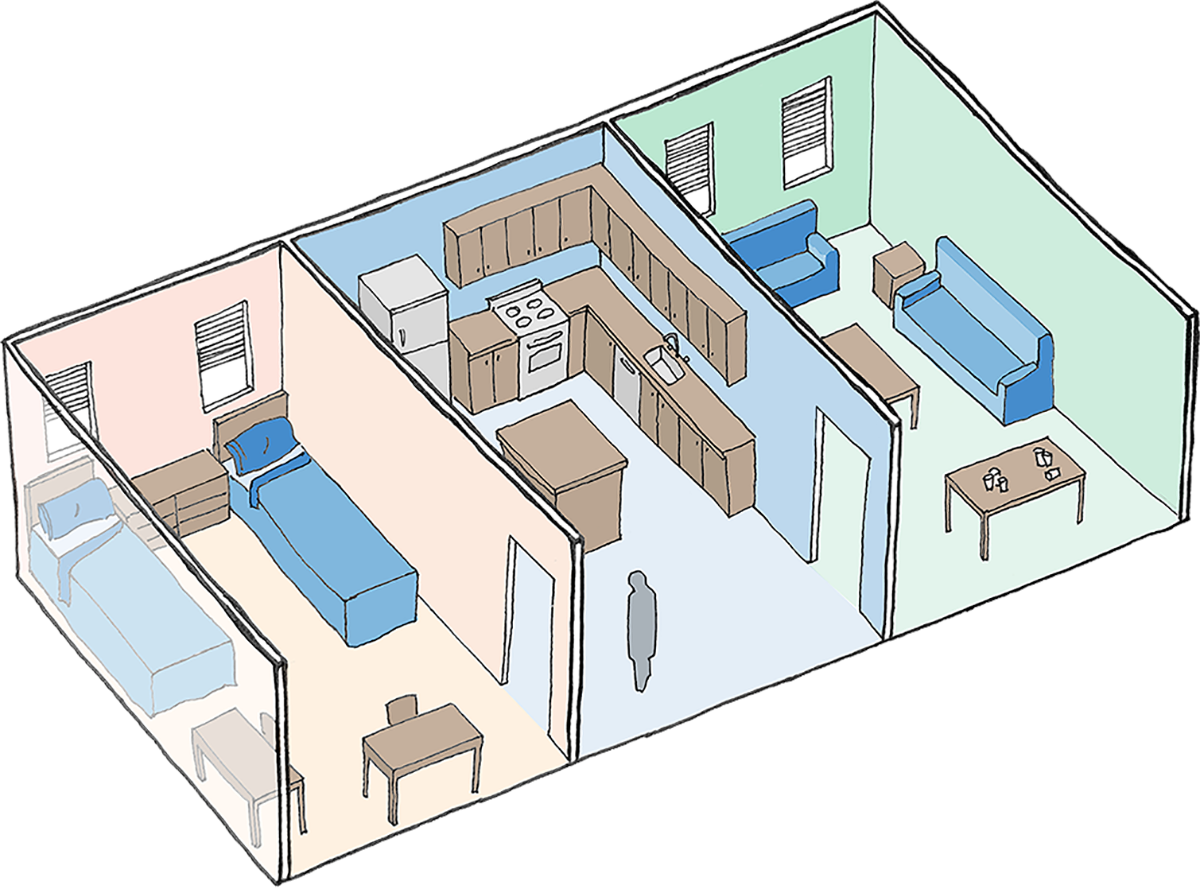

Dorms

Click the icons below to learn more about dorm rooms affect residents’ mental health.

Social

It’s easy for students who live alone off-campus to feel lonely and disconnected from the college community.

“Isolation and lack of social support increase the risk of depression,” Sarah William Goldhagen writes in Welcome to York World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives, citing research by doctors George Engel and Franz Reichsman. “Positive social interactions are important buffers against stress.”

The first step in combating loneliness is normalizing it.

“It doesn’t make you crazy. It doesn’t mean you’re different. We all go through it,” says Mackenzie Rondeau, a former resident advisor at Sacred Heart University. “Figure out the type of people you want to be surrounded by, like people who have similar interests.”